Finding Eric

The difficulty in finding something in the forest that doesn't want to be found

In previous TSB posts I speculated how a Bigfoot species could remain undiscovered. In The Inconvenient Bigfoot I wrote about difficulties in capturing a photo or video of the great beasts. In The Pattern-seekers I wondered what survival (and avoidance) capabilities a Bigfoot species could have mastered during millions of years of evolution. In Reality is an Onion I considered whether there exist properties of forest ecosystems familiar to Bigfoot but not to us. And in Bigfoot Are Meta I proposed that Bigfoot exist in small, mobile groups moving vast distances between and among habitable patches of forested areas. These and other posts have led us here, and they can help us take what we learn from Eric and apply it to Bigfoot.

The case of Eric

Eric is a Christian terrorist from Florida. He believes that killing people is the most productive way to share his god’s message. In the later part of the 20th century, acts of blowing up innocent people were in vogue as a form of mass shock communication.

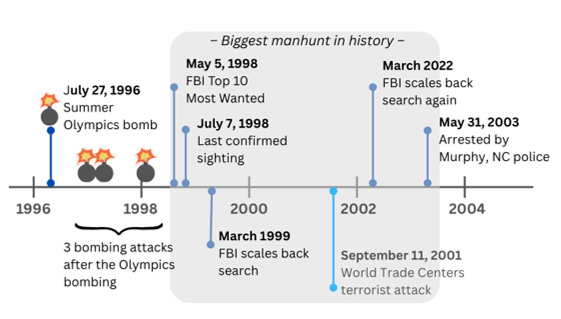

The timeline below shows milestones regarding Eric’s case from 1996 to 2003. I’m sure Eric did other things before 1996, but most likely those involved poor role models and bad decisions that led him to terrorism.

Eric’s belief system is an amalgam of anti-gay, anti-government, and anti-abortion sentiment. He’s a good fit with right-wing extremists, somewhere between Timothy McVeigh (the Oklahoma City bomber) and January 6 rioters. He’s probably closer to the latter. He would have blended in with zip-tie guy, the guillotine maker, and the pipe-bomb planter.

A June 2003 article in The New York Times described Eric as “a white supremacist and skilled woodsman.” An odd mixture, for sure. A man conditioned to both hate and survive.

I’m not interested in Eric’s bombing history, though by the end of his jihad Eric detonated bombs on four occasions. The first three events happened in Atlanta, Georgia, and the fourth happened in Birmingham, Alabama. Not long after the fourth bombing, the FBI put Eric on their infamous Top 10 Most Wanted list. This is where things get interesting, and where we can learn something about the forests in North America.

The search for Eric

A May 2018 article in Blueridge Ridge Outdoors by Kim Dinan referred to the hunt for Eric as “The biggest manhunt in history.” This might be a stretch, though it depends on how one measures “bigness.” There’s lots of competition in the big-killer-manhunt category, even in the US alone. There’s the Unabomber Ted Kaczynski and the MLK Jr. assassin James Earl Ray, not to mention serial killers such as David Berkowitz (aka the Son of Sam) and Ted Bundy. So maybe Eric’s wasn’t the biggest, but it’s certainly high on the list. Dinan nails the cost to hunt down Eric at $24 million while a CNN article by Henry Schuster and Brian Cabell (March 2002) goes as high as $30 million. In 2025 dollars that’s about $50 million.

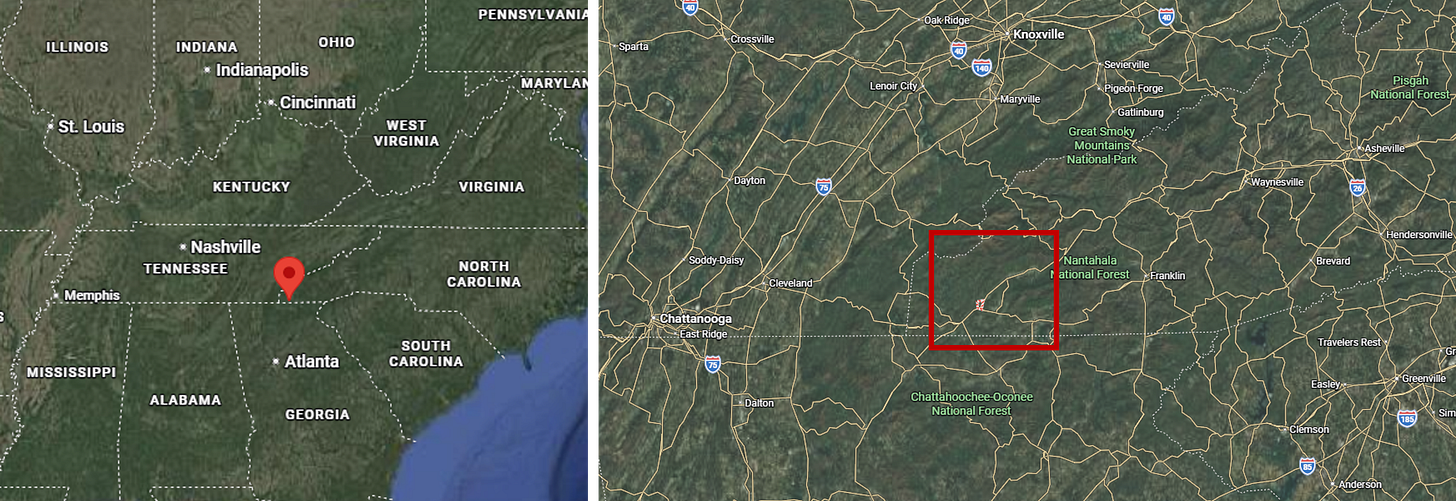

As for the human resources, the FBI formed the Southeast Bombing Task Force in 1998. The force grew to as many as 200 dedicated agents, searching 500,000 acres in and around Murphy, North Carolina and the Nantahala National Forest1.

For context, the US Census Bureau says North Carolina covers 48.6 thousand square miles, which converts to roughly 31.1 million acres. So, the FBI pinned Eric to an area equivalent to just 1.6% of the state of North Carolina.

From a broader perspective, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2025 opened 112 million acres of national forest to logging (check out this Wes Siler’s post on Substack for details). That’s 211 times as much forest as the Nantahala National Forest (which is roughly 531,000 acres) and 3.6 times the size of North Carolina. The United States is a big place with a lot of forests, and the FBI covered just a fraction of it in their search for Eric.

Dinan (2018, cited above) offered one of the richest descriptions of the search for Eric:

But before that day [Eric was arrested], there were five years that preceded it. Five years where the FBI scoured the Nantahala National Forest with bloodhounds, electronic motion detectors, and heat-sensing helicopters. They set up listing posts with cameras and hired local scouts to tromp through the woods with gridded maps. They named Eric Robert Rudolph to their Most Wanted List and put a $1,000,000 price tag on his head. That’s when the bounty hunters came crashing into town, determined to make a fortune off of finding Rudolph.

A New York Times article by Jeffrey Gettleman and David M. Halbfinger in June 2003 said of the hunt:

In the spring of 1998, the F.B.I. sent hundreds of camouflaged agents to scour every inch of the Nantahala National Forest, on the edge of the Appalachian trail. They employed bloodhounds, electronic motion detectors and helicopters with heat sensors, aerial maps, local guides, hunters and volunteers.

The search for Eric may not have been the biggest but it was pretty damn big.

Early enthusiasm to find Eric soon diminished. According to Dinan (2018):

By 2000, the search had been scaled back. By the spring of 2002 there were only a dozen agents on the case. A year later, there were only two agents in Asheville coordinating a team of paid scouts. There was speculation that Rudolph had died somewhere out there in the dense, wet woods.

I suppose after all that effort to find something, and nothing is found, it’s a natural inclination to believe it no longer exists… or that maybe it never did.

But the FBI and its cadre of searchers wasn’t just up against a dense forest and rugged terrain. The local communities had their own way of making things more difficult for the Southeast Bombing Task Force.

Local support for Eric

Several articles on the case position the people of Murphy, North Carolina and surrounding areas as ambivalent toward Eric and distrusting toward federal agents2. I imagine the situation was something like US communities of today reacting to ICE agents rolling into their towns and neighborhoods.

In Eric’s case, locals held conservative views and tended to align with his extremist ideology, at least to some extent. They sided with him on anti-abortion and anti-government attitudes. In this sense, they viewed Eric as unfairly condemned by a corrupt government. Some even sold t-shirts reading “Run Rudolph Run”3. The FBI on the other hand viewed the local communities as guarded and adversarial.

At the same time, however, the task force received hundreds of tips, though none led them to Eric. In an interview posted on fbi.gov, Former FBI executive Chris Swecker described Eric as a “loner” and that the FBI “strongly believed he simply wouldn’t have trusted anybody.”

Eric’s strategy to remain undiscovered

Aside from the usual outfitting that goes into preparing for a jihad, Eric planned for his inevitable fleeing from law enforcement. FBI.gov said that Eric lived off the land and whatever resources he could sequester from local food supplies. He had a cache of food barrels in the woods, and he stowed away for later whatever he could steal from restaurant dumpsters and grocery store loading docks. He utilized vacant mountain cabins in colder months.

According to Dinan’s (2018) research, Eric had two main camps: one where he could observe FBI operations and the other a secluded camp deep in the forest. Dinan quotes the Sheriff of Clay County, Tony Woody, as saying of Eric’s more secluded campsite, “you could walk within 10 feet of it and never see it.”

Imagine that. You could walk within 10 feet of an established campsite and not even know it. It’s no wonder that Eric got himself caught not by a search team armed with deep-woods experience and advanced technologies but by his own diminishing resolve and exhaustion.

Eric was arrested in May 2003, nearly 5 years after the last confirmed sighting. He was found late one night digging through a Save-A-Lot food store trash bin by a 21 year-old rookie police officer. The Murphy, North Carolina police described Eric as “relieved to no longer be on the run.” Eric pleaded guilty to the bombings and is serving multiple life sentences.

Why does this matter to TSB?

In a 2024 article in the Skeptical Inquirer, self-styled skeptic Benjamin Radford addressed the controversy over the iconic Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot film, particularly the ongoing debate about why no one has been able to convincingly recreate the Bigfoot footage from 1967.

In criticizing the Patterson-Gimlin film, Radford offers a response to Bigfoot proponents who say the inability of skeptics to reproduce the film is evidence to support the film’s authenticity. Radford says (and I had to read this twice to be sure I read it correctly):

It’s not that no one could do it; instead, understandably, no one has bothered investing the time, expense, and effort into a replication project that has no chance of definitively settling the matter. (Radford, 2024)

For me and most true skeptics, an accurate reproduction would settle the case quite definitely. “I could do it, but I don’t want to” is the most bullshit, grammar-school-playground excuse for not doing something. Two broke cowboys did it nearly 60 years ago, and the film continues to be perhaps the most controversial piece of evidence in all cryptozoology.

Radford pushes back on the Bigfoot proponents. He says with not-so-subtle condescension, “If these Bigfoot creatures are really out there wandering in front of eyewitnesses with cameras, why haven’t better films and videos emerged in the past fifty-seven years?”

One answer to Radford’s deflection is that there are videos out there. I argued as much in The Inconvenient Bigfoot. We have to sort through the clutter, the hoaxing, and the disinformation to find that good evidence. For the curious, here’s a detailed review of three such cases that are just as divisive as the Patterson-Gimlin film. Even if Radford took time to watch these videos, he’d probably say each is a hoax and then argue he could reproduce them but it’s not worth his time to do so.

For a second answer to Radford, we can return to Eric. Finding something in the forest is difficult. A government-sponsored and organized search covering a defined area of land with significant human and technical resources could not find Eric for five years. Even then, it’s arguable that Eric let himself be found out of sheer weariness from the chase. Why would an informal, loosely-organized community of hobbyists be expected to have more success in finding a Bigfoot?

The bottom-line

Despite Eric’s skill as a survivalist, he remained connected to society and dependent on it, at least in part, for food, clothing, and technology. But even with this reliance he evaded hundreds of law enforcement officers, volunteers, scouts, bounty hunters, local guides, helicopters, bloodhounds, heat sensors, and motion detectors, all in a coordinated effort to find him in a finite area of western North Carolina.

Did the locals help Eric? Yes, but not directly, in my opinion. And just as anti-government, anti-abortion sentiment gave locals a reason not to help in the search for Eric, many Bigfoot witnesses withhold their encounters to protect their private property, favored hunting grounds, or reputation in their social group.

If Eric teaches us anything about Bigfoot it’s that finding one in the forests of North America is not as easy as self-styled skeptics would have us believe. How many agents and scouts walked within a few feet of Eric without knowing he was there? How many hunters and hikers walked within a few feet of a Bigfoot without knowing it was there?

Next time on TSB

The USDA order to open 112 million acres of national forest to logging is a complicated issue. Read Wes Siler’s post for a closer look. I imagine there are significant implications for a Bigfoot species, depending on whether that logging is done “right” or “stupidly,” to use Wes’s words. If Bigfoot exist and have survived through metapopulation dynamics, then I fear we’ll discover them too late or we’ll never know they existed at all. But that’s for another time on TSB. I’m ready to get out of the forests and back into the brains of witnesses. So next time I’ll explore psychosis as a possible explanation for reported Bigfoot encounters. In general, I don’t think this debunker argument will help us in our quest for the truth about Bigfoot. However, there is one form of psychosis that may get us a little closer. Until then, troopers, keep to the trails.

Thanks for reading and don’t be a Stranger,

DC | TSB

Henry Schuster, May 31, 2003. FBI: Olympic bombing suspect arrested. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2003/US/05/31/rudolph.arrest/

See for example, Kevin Sack, July 24, 1998. Elusive Bombing Fugitive Divides a Town. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/24/us/elusive-bombing-fugitive-divides-a-town.html

David M. Halbfinger, May 31, 2003. Suspect in ‘96 Olympic Bombing and 3 Other Attacks Is Caught. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/31/national/suspect-in-96-olympic-bombing-and-3-other-attacks-is-caught.html