The most devastating argument

If Bigfoot exist, where are all the bones?

David Daegling, anthropologist and author, described this question as “the most devastating argument against Sasquatch.”1 Daegling goes on to say that the main counter argument by what he calls Bigfoot advocates is that nature has a way of ridding the forest floor of the dead. Flies, beetles, coyotes, vultures, time... the whole works. Les Stroud offered this defense during his interview on the Joe Rogan Experience in 20122:

So that’s a question, right? “How come you never find a skeleton?” I’ve been in the woods for many, many years and I’ve never in my life come across a black bear skeleton, and there’s 60,000 of them in Ontario alone.

Daegling refutes the advocates by sharing a personal anecdote about finding a partial bear skull in the wild while walking with a colleague in 1997.

What was unusual was that no other parts of the animal were visible nearby, perhaps having been carried off by scavengers. In any case, all we had was this half skull. But the point is, we found it. We had walked through the landscape over the course of perhaps ten days, but on this day we stumbled on the remains of a bear by dumb luck alone; we weren’t even looking for fossils at the time. (from Bigfoot Exposed, p 194)

I don’t know. I suspect the black bear population would far outnumber a Bigfoot population, so the odds would be much less than dumb luck that someone would stumble upon a Bigfoot skull. Anthropologist Grover Krantz speculated in his book Bigfoot Sasquatch Evidence3 that the Bigfoot population could be around 2,000 in the Pacific Northwest and possibly 10,000 to 20,000 across all North America. Of course, the counter is that Bigfoot bones are much larger and denser than the smaller black bear, so their bones would persist much longer in nature. The counter-counter would probably focus on the general absence of Gigantopithecus (the supposed extinct super-sized orangutan) bones beyond a few teeth and jawbones, so maybe nature doesn’t discriminate based on bone size or density. Round and round the debate would go.

Beyond the bones

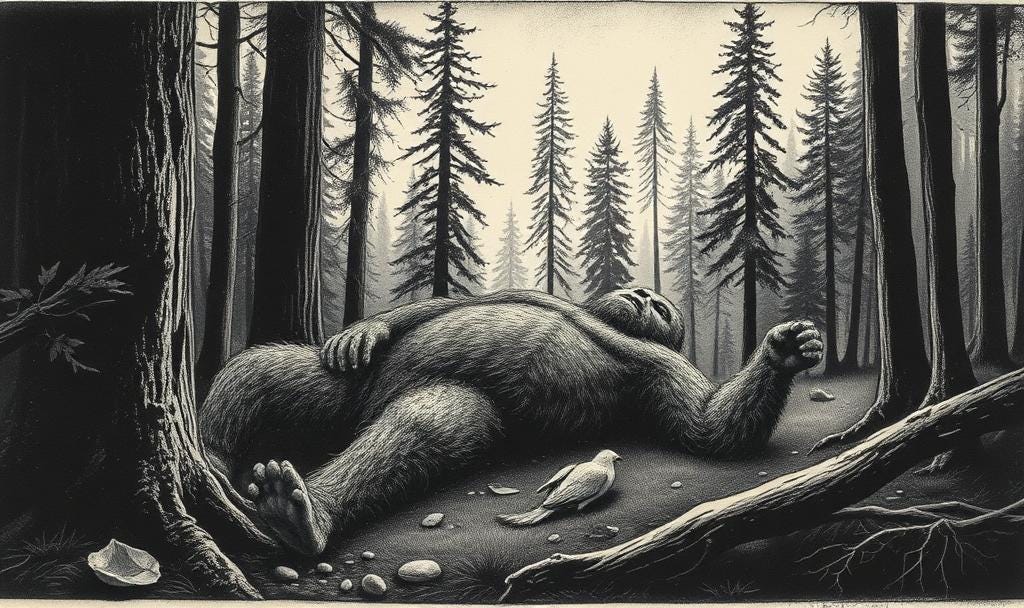

The near impossibility of finding black bear bones goes a long way toward explaining the absence of Bigfoot bones. But even within the social world of Bigfoot this proposition falls a little short, which is likely why I hear speculation that Bigfoot may actually bury their dead. At first, this seemed like a straw man argument borne of convenience and desperation; I mean, the image of Bigfoot digging holes to bury their dead is difficult to contrive. But is this idea really that implausible? Look at this way:

I have lived in 5 states across the US, and I have traveled to most other states. I have spent countless hours in places humans congregate, such as airports, shopping centers, restaurants, public parks, suburban neighborhoods, urban downtowns, and small town main streets. In all my wandering about I have never come across any human bones. If humans exist, then where are all the bones?

Certainly there are human bones and of course humans exist. I am not suggesting otherwise. We humans have created institutions to care for our dying and our dead. To believe that humans are the only species to understand and respond to death is a bit species-ist (I’m half-coining a term here). The view that humans are unique and that only humans are capable of understanding death is a form of speciesism, or discrimination based on species. Its like ageism or sexism but more generalized to entire species. God, we love to hate, don’t we? But don’t feel bad if you share this view about non-human animals in matters of death. Even among scientists this has been a dominant view. Until recently, that is.4

The science of death

The study of how humans respond to death is called thanatology; how species differ in their response to death is referred to as comparative thanatology. Side note: As a modest fan of the Marvel Universe, the similarity here to Thanos is not lost on me. In fact, the root of thanatology comes from the Greek word thanatos, which means the personification of death5. That’s dark… but poetic.

If we treated our dead like most forest dwellers, we’d leave bodies wherever they drop, or watch our dying comrades crawl off to an isolated spot. And we’d find human bones everywhere. Sidewalks, parking lots, back alleys, gas station bathrooms, bus stops, front lawns, and so on. But as intelligent, social animals we care for our dead. We follow ceremonies and rituals — those unwritten but mutually understood rules that define this bitter reality of existence. We bury or cremate our dead to get closure for the living and to protect our communities from diseases and pathogens that rise from decay.

Truth is, we homo sapiens have become exceedingly efficient at handling our dead. We get a lot of practice. Roughly 9,000 people die each day in the US. That’s comes to 375 each hour6. But we’re not the only species to recognize and respond to death in predictable ways. Many other species also do this, especially large-brained, social ones. Heck, even some tiny species do this.

I am not proposing there’s a Bigfoot wonderland with long-term care hospitals, crematoria, and cemeteries. Rather, I’m merely proposing —as others have in far fewer words— that the Bigfoot species could respond to deceased members of their troop in a manner somewhere between humans and other intelligent species.

How other animals respond to death

In 2016, James R. Anderson — a leading thinker in thanatology— published an overview of comparative thanatology7, where he outlined the current state of the science and what researchers have learned about how various species respond to the death of conspecifics — which is just a fancy word to refer to members of the same species. A core research question is whether other species have a cognitive capacity to understand death as an inevitable and irreversible part of living.

Much of this research explores how non-human primates and other large-brained animals respond to the death of an infant or juvenile conspecific. Researchers Andre Goncalves and Dora Biro (2018) summarized the behavior of non-human primates under this condition as “mobbing/alarm calling, aggression, dead infant carrying, vigils and visitations of the corpse.”8 In their paper, the researchers offer a rundown on a range of species.

Eusocial insects (that is, insects with complex social structures such as ants, bees, and termites) respond to chemicals released by dead conspecifics and either bury the dead, remove the corpse from the nest, or place it into a special chamber. Researchers have dubbed these clean-up workers as “undertakers.”

For intelligent bird species (aka. corvidae which include crows, ravens, and jays, among others), there are reports of a loud calls and gatherings near deceased conspecifics.

Asian and African elephants have been observed surrounding a dead conspecific and interacting with it. Behaviors include touching, vocalizing, and even attempting to lift it up. Elephants have also been observed covering them with leaves or soil.

Whales, dolphins, and porpoises have been observed interacting with or carrying dead calves or juveniles. In many cases the pod are observed swimming with or surrounding the mother and dead calf.

Other animals that interact with or carrying their dead infants for extended periods of time including giraffes, otters, dingoes, seals, sea lions, and manatees.

For insect and bird species these behaviors are considered unemotional or mechanistic rather than part of a grieving process. The chemical stimulus-response behavior drives insects to protect the nest from pathogens that could emanate from the corpse. The gathering behavior among corvidae seem to have the purpose of acquiring information that could enable the continued survival of remaining flock members. This information could pertain to nearby threats or who in the flock is suddenly available for mating.

For the larger species, researchers argue these behaviors could indicate a cognitive capacity to understand death to at least some degree, more so among non-human primates.

What this means for Bigfoot

Much of thanatology is data gathering through observation of wild or captive animals. There's a lot of interpretation and judgment by the researchers, so for now we really only have untested theories about what's really happening in the brains of these animals. Why do they do what they do when they do it? Honestly, we have enough trouble trying to figure out our own personal motivations for what we do. Why the hell and I'm writing about Bigfoot, anyway? This could take years to figure out, or maybe one day in the middle of writing a post I'll figure it out, like when Forest Gump just stopped running: he felt he had run enough.

Still, researchers are discovering variation across animal species when it comes to death among their companions. In particular, animals with larger brains exhibit behaviors that suggest a level of comprehension regarding death. Its no longer humans in one camp and all other living creatures in another camp. Rather, its a continuum of understanding that ranks humans at the top (maybe) followed by non-human primates, other large-brained animals, and so on down the list.

If Bigfoot are hominin or hominid — that is, a known or unknown human or great ape species — as one of the theories I wrote about last week proposes, we might expect Bigfoot to respond to death in a way that is more similar to humans than to smaller-brained animals in the forest, say black bears. Its not a ridiculous notion that Bigfoot take care of their dead, whether to protect the troop from unwanted attention, to save their departed from predation, or as part of a complex grieving process not much different from homo sapiens.

While the analogy to bear bones in nature is a valid starting point, the lower population of Bigfoot combined with behaviors toward the death of conspecifics would dramatically reduce the odds of discovering their bones by dumb luck or even a purposeful search, for that matter. The “no bones == no Bigfoot” argument is not as devasting as many people believe, after all. But then again, nothing is simple about Bigfoot.

Next week on TSB

We’ll tackle more theories about Bigfoot. We’ll get deeper into the social sciences and examine how some debunkers use superficial and misleading interpretations of the science to make their points, and how a closer analysis of the science shows the opposite of what debunkers claim. Buckle up, folks. This could get a little prickly.

Thanks for reading and don’t be a Stranger!

DC | TSB

Daegling, David, 2004. Bigfoot Exposed. p 193.

I mentioned this interview in my post “A Stranger and a Regular Walk into a Bar”. You can find the interview here. The Bigfoot discussion starts around the 1:03 mark (H:MM): https://archive.org/details/vimeo-53990449

Krantz, Grover, 1999 (reprint). Bigfoot Sasquatch Evidence. Original edition in 1992. The quote that follows in the post is from p 162.

I really liked the introduction to this 2022 paper from Arianna de Marco and her colleagues: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03949370.2021.1893826

To get some history around thanatology, go here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thanatology

Its coming for each of us, eventually. https://northamericancommunityhub.com/how-many-people-die-every-day-in-the-us/

For a reasonably short introduction to comparative thanatology, see this quick guide by James Anderson here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982215013718

You can find the Goncalves & Biro article here: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2017.0263